This article is a summary of Kevin Maney’s and Mike Damphousse’s fireside chat at the Strike Marketing Summit on December 11, 2025. Kevin and Mike are the co-founders of Category Design Advisors and authors of the upcoming book The Category Creation Formula: Discover, Design, and Win New Market Categories, published by Harper Business on February 24, 2026. Pre-order the book here.

On December 11th, our Strike Marketing Summit audience got something rare: a first look at ideas that nobody else has seen yet.

Kevin Maney — former USA Today technology columnist, co-author of the landmark book Play Bigger, and one of the most respected voices in business strategy — joined his partner Mike Damphousse for a fireside chat that gave our attendees a preview of their new book before its public launch.

Mike is a computer scientist turned startup CEO and CMO with several exits under his belt — including an IPO on the Tokyo Stock Exchange — who had been running in the Play Bigger crew's orbit for years before teaming up with Kevin to form Category Design Advisors in 2016.

Kevin and Mike have spent nearly a decade running Category Design Advisors, working intimately with over 50 companies and consulting with thousands more through VCs and incubators. The new book packages everything they've learned into a playbook that any founder can follow.

What they shared that day reframed how I think about category design — and I suspect it’ll do the same for you.

The Formula That Explains Every Great Product Launch

Here’s the core idea. After years of working with companies ranging from two-person startups to LinkedIn’s billion-dollar sales division, Kevin and Mike distilled category creation down to a formula:

Context + Missing + Innovation = New Market Category

It sounds simple. It’s not. But it is elegant, and once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

Context is what’s changing around the audience you’re trying to serve. Not just technology — though that’s often a big piece — but also shifts in politics, the economy, culture, regulations. Anything that’s reshaping how your audience operates.

Missing is the gap that the new context creates or exposes. What problem has emerged that isn’t being solved? What old problem can suddenly be solved in a new way?

Innovation is the solution that fills that gap. But here’s the key: you’re not describing your product. You’re describing the category — the new way of doing things that needs to exist whether you build it or not.

To make this concrete, Kevin walked us through how Steve Jobs used this exact formula — whether he knew it or not — when he introduced the iPad.

Jobs got on stage and started with the context: there’s a new digital media landscape. Everything is going digital — music, books, movies, sports, all of it. Then he pointed to the missing: you have two devices to consume all this content. A phone with a great but tiny screen, and a laptop with a big screen that you’d never take to the beach. He made the audience feel the gap. And then — only then — he introduced the innovation: a new category of computing called a tablet. Apple’s version was the iPad.

Context. Missing. Innovation. New category.

Kevin told us that if you study every product launch Jobs ever did, the structure is the same. And it’s the same formula Kevin and Mike now use as the very first exercise when they sit down with a new client.

Landing in the Adjacent Possible

One of the most powerful concepts from the session — and one that wasn’t in Play Bigger — is something Kevin and Mike call “the Adjacent Possible,” adapted from Steven Johnson’s book Where Good Ideas Come From.

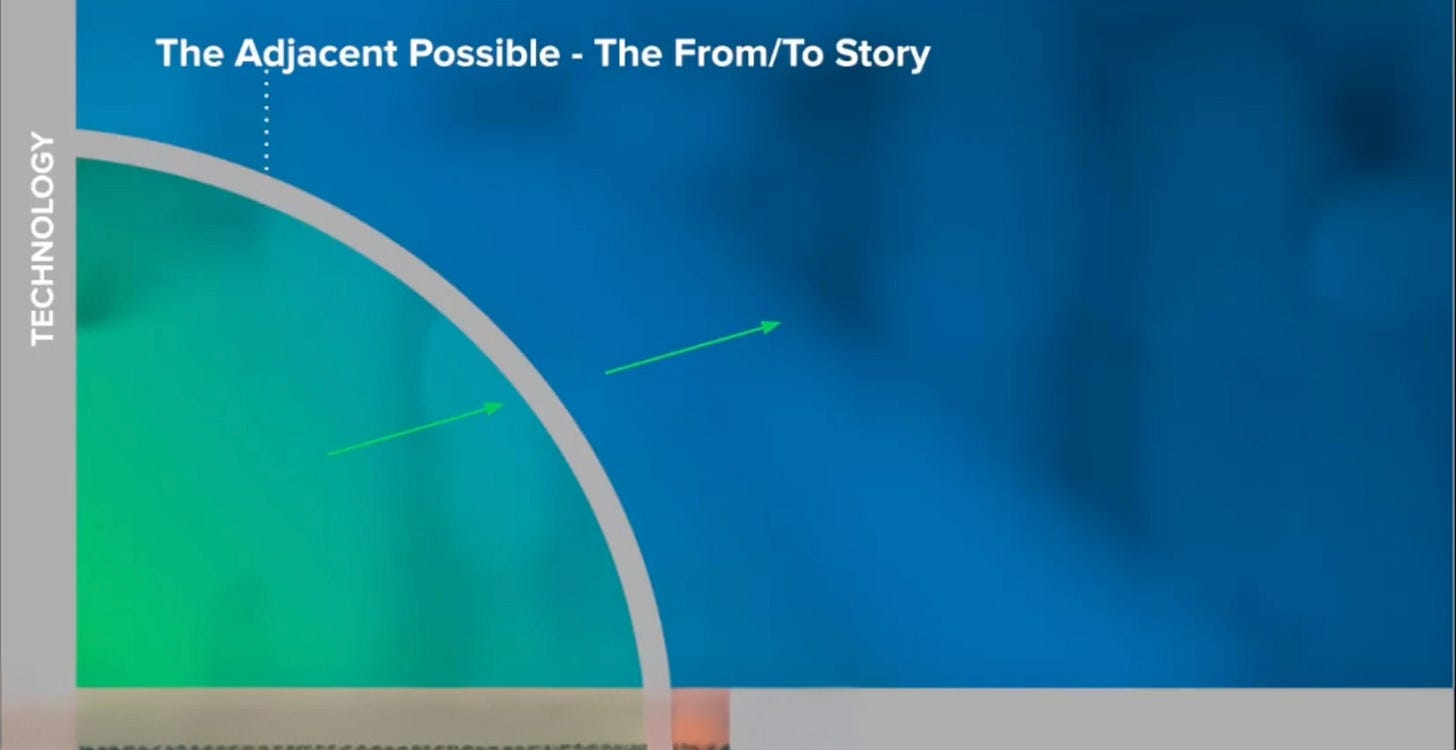

Picture a chart. The vertical axis is technology — what’s technically possible. The horizontal axis is society — what people are ready to adopt. The green zone is everything that already exists and works: your laptop, your phone, your toaster. The blue zone is stuff that isn’t viable yet — the technology is too buggy, too expensive, or people just don’t get it yet. Quantum computing lives in the blue zone.

Between those two zones is a thin band: the adjacent possible. That’s where breakthrough categories land. The technology works well enough, and people can grasp why they need it — but it’s new enough to feel exciting and different.

This framework gives founders two critical diagnostic questions. First: are you in the green zone? If so, you’re just entering someone else’s category and competing on price or features. You need to push outward. Second: are you in the blue zone? If your vision is ten years ahead of what the market can absorb, you’ll run out of money before it matters. You need to pull backward.

Kevin illustrated this with Jeff Bezos. In 1994, Bezos knew the internet would become a platform for selling everything. But people were still afraid to put their credit cards online. An “everything store” was deep in the blue zone. So he found his adjacent possible: books. There was a specific audience of book lovers who couldn’t find what they wanted in local stores. Amazon could find any book anywhere and ship it to them — even if it took two weeks. That was enough. It landed in the adjacent possible, and Bezos painted the journey from there.

That’s the other critical insight: category design isn’t just about where you land today. It’s about the journey you promise to take people on. Bezos’ early investor letters always described the progression — books first, then everything else. The journey is part of the story.

Set the Rules, Own the Category

Here’s a concept that Kevin emphasized as entirely new — not in Play Bigger at all. When you create a category, you should set the rules for how it works. And if you set the rules, you’re always in charge.

The example that makes this visceral is Uber. Go look at Uber’s very first VC deck — it’s still floating around the internet. In that deck, they defined how ride-sharing would work: a little map showing nearby cars, a pin to set your pickup, automatic credit card payment so you never fumble for cash. There could have been a hundred different ways to design a ride-sharing experience. Uber picked one and declared it the standard.

Now open any ride-sharing app anywhere in the world — Singapore, São Paulo, Lagos — and it basically looks like Uber’s original vision. Because Uber set the rules, every competitor had to follow them. And when Uber changes the rules, everyone else has to adapt.

For founders, the implication is direct: your category rules are one of your most valuable strategic assets. What expectations are you setting for how your category works? What must every player deliver? Define those early, and you become the reference point for the entire space.

Name It Right: New Word + Old Word

Kevin shared a research finding — from Princeton, if he remembered correctly — that transformed how they approach category naming. The researchers studied which new names actually stick in culture, and found a clear pattern: the ones that pair a new word with an old word.

The old word anchors you in something familiar. The new word makes it feel different and fresh. Together, they pull the concept into the adjacent possible.

Think about it: we all knew what a phone was, then “smart” made it a new category. “Computing” was familiar; “cloud” made it something else. “Oven” was boring; “microwave” made it revolutionary. When Kevin and Mike worked with LinkedIn, they created “deep sales” — everyone in the sales profession understood “sales,” but “deep” signaled a fundamentally different approach.

And here’s the critical guardrail that came up during our chat: your category name is not your brand name. You should never trademark it, never capitalize it as a brand, never present it as proprietary. You want other people to use it. I shared the cautionary tale of Mexico’s Softtek, which coined the term “nearshoring” — a brilliant category name — but made the mistake of trying to trademark it. Today everyone from Mexico to Tierra del Fuego uses the term, and the trademark is essentially meaningless. That’s actually a category design success: the name belongs to the world. Your brand wins by being the one everyone associates with the category.

The POV Structure That Works Every Time

After years of writing points of view for dozens of companies, Kevin and Mike have landed on a structure that’s become formulaic — in the best sense of the word. It mirrors the category creation formula itself:

First, you deeply describe the problem. This is the context piece — you make the reader feel the weight of what’s changing and what’s broken. Second, you define the solution — and this is about the category, not your product. It’s not a marketing document; it’s a category document. Third, as part of that solution definition, you set the rules — the expectations for how this new category works. Fourth, you paint the journey — where this category goes in three to five years, the progression you’re promising. And finally — and Kevin stressed this is the least important part — you explain why you’re positioned to lead this. If you’ve done the first four well, this last piece almost writes itself.

The Biggest Misconception: This Isn’t Marketing

When I asked about the most surprising lesson from their decade of practice, Mike’s answer was immediate: the biggest misconception about category design is that people think it’s a marketing exercise.

It’s not. It’s a strategic company initiative that should be led from the CEO’s office. Marketing will be the tip of the spear and handle much of the execution, but category design is not a messaging project, not a positioning project, not a branding project. Those things all stem from category design. They’re outputs, not the work itself.

Kevin reinforced this with a powerful anecdote. After finishing a major category design project for an insurance technology company, Mike asked the executive team how they were feeling. One executive said he felt “embarrassed.” When they asked why, he said: “I’m embarrassed that we couldn’t do this on our own. We knew all this stuff and we couldn’t do it.” Kevin compared it to therapy — you know yourself better than anyone, but you still need someone in the room to make the breakthrough happen.

When Is the Right Time? Now.

Mike addressed the question they get most often: when should we start category design work? His answer: if you think you have a category, do the work now. Don’t wait.

Because if you wait, the market will define you. Mike invoked the Mike Tyson analogy from Play Bigger: somebody’s going to tattoo your face with who you are — you’d better beat them to it. Whether you’re two people with a credit card and a startup idea or a 15-year-old company like LinkedIn, the right time to design your category is always now.

But Kevin added an equally important counterpoint: category design is a long game. You don’t write a POV, do one lightning strike, and declare victory. In the new book, they dive deep into the work of economist Paul Geroski, who studied how market categories actually play out over time. The research reveals why you need sustained, repeated strikes and what Kevin and Mike call “heartbeats” — consistent signals over a long period — to establish yourself as the category winner. It’s not a sprint. It’s a commitment.

Stories From the Trenches

The session was full of compelling stories, but one stood out as the kind of narrative that makes category design feel less like abstract strategy and more like a path to something meaningful.

GuideWheel was four or five people when they came to Category Design Advisors. The founder, Lauren Dunford, had worked in manufacturing and — through her husband, who was from Kenya — had seen firsthand how thousands of small factories around the world couldn’t afford the technology that makes large manufacturers efficient. Her team developed a $25 clip that attaches to the electrical cord running into any factory machine. The clip reads the electrical signal, sends it wirelessly to a cloud-based analytics platform, and can predict when a machine is about to fail, identify inefficiencies, and help small manufacturers operate like the big players — all while reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Kevin and Mike helped them frame this as a new category. The company loved it so much they changed their name. And Lauren ran with the POV so effectively that the World Economic Forum invited her to speak. Then TED invited her to their main stage. The talk is on YouTube now. A company that started with five people and a sensor clip is now, as Kevin put it, “on fire.”

That’s what category design makes possible. Not just a better pitch — a platform for an entirely different trajectory.

What This Means for You

Everything Kevin and Mike shared that day reinforced the foundation of what we teach at Strike Marketing: category design isn’t optional for founders who want to escape the invisibility trap. It’s the starting point.

The Category Creation Formula gives us a shared vocabulary — context, missing, innovation, adjacent possible, category rules — and a process that’s been tested with over 50 companies across a decade. Whether you’re a second-act founder launching something new or a seasoned operator who knows your current positioning isn’t working, the formula applies.

Kevin and Mike’s book, The Category Creation Formula: Discover, Design, and Win New Market Categories, comes out February 24, 2026 from Harper Business. You can pre-order it now at thecategorycreationformula.com. And if you want to talk to them directly, they offer free office hours at categorydesignadvisors.com/book-office-hours — they talk to 150 to 200 companies a year and genuinely enjoy it.

This was one of the most valuable sessions from the Strike Marketing Summit — and it was only the beginning. Stay tuned for more recaps from the event, including how to build an event engine that drives 700% growth and why founder-led content is the ultimate competitive advantage.